"Leave me alone! I live here!"

If any statement might describe Billy Frank, Jr.'s life, that might be it. Frank shouted it at the age of 14 as he was being arrested for checking a fishing net in WashingtonState's NisquallyRiver. Frank, and all Nisqually tribe members, know fishing in the river their right—not only because it's a major part of their traditions but also because it was guaranteed by treaty. The Nisqually tribe is by US law a sovereign nation.

Nonetheless, the US game wardens didn't share that view, and Frank was arrested. He'd be arrested dozens more times over the next several decades.

The Treaty of Medicine Creek was signed in 1854. It was a terrible deal for tribes: The state of Washington took away over two million acres of their land and left them about a thousand acres on a bluff west of the Nisqually River. However, it did leave them this: the right to take fish "at all usual and accustomed stations . . . in common with the citizens of the Territory." The tribes were forced to accept the treaty.

Over the years, various local and regional governments took away more land from the Nisqually. And then came logging and development, damming of the river, diversion of water, pollution, and hundreds of non-Native commercial gill-netters and purse-seiners. Indians were catching less than five percent of harvestable salmon—and even then they often had to do it secretly because of anti-Indian sentiment. Recalled Frank, "To survive, to continue our culture, we had to become an underground society." Frank relates incidents "of having boats and nets confiscated, of being chased and tear-gassed, tackled, punched, pushed face-first into the mud, handcuffed, and dragged soaking wet to the county jail."

In the 1960s and 1970s, Frank led Natives in "fish-ins"—protests on three local rivers, all in the face of assaults and arrests. Demonstrations followed, as well as legal action. Eventually, it was the legal action that made history.

On February 12, 1974, in U.S. vs. Washington, Judge George Boldt found that 20 Indian tribes in western Washington were indeed entitled to half the harvestable salmon and that they should co-manage the resource. The "Boldt Decision" was upheld five years later by the U.S. Supreme Court. It was a clear and convincing Native victory. And it wouldn't have happened without the fish-ins.

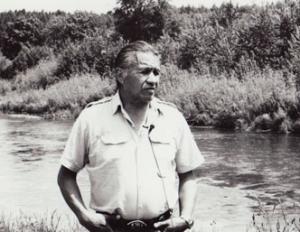

For the next 30 years, Frank was chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, now waging a different battle—the battle to preserve salmon and other fish in the Nisqually. Even though Frank acknowledged that "I wasn't a policy guy; I was a getting-arrested guy," he led the way to many policy decisions that helped to ameliorate some of the ill effects that the dams and pollution had had on endangered salmon. The commission also managed fisheries and restored and protected other habitats. Frank was seen, appropriately, as spokesman for the commission. He wrote many editorials, served on many councils, and advised many people on topics related to Native rights and preservation of native habitats.

Billy Frank's wife, "Being with Billy is like floating on a steady, easy river. Billy's life is turbulent, but Billy is not. He's the happiest person I know. He's completely at peace with himself."

We're thinking that Frank was more at peace with himself after the federal government acknowledged that the Nisqually was in fact his people's land and that US law officers should in fact leave him—and the other Native fisherman—alone.

Update: