Picture it: It’s 1984, and for the past six weeks you’ve been laid up in a Little Rock, Arkansas, hospital. You’re very sick; in fact, you’re dying. But even though you’re hospitalized, you’re not really being cared for. The nurses draw straws to see which of them has to enter your room. You’re not contagious, but for some reason everyone thinks you are. Your own mother refuses to visit you, and right now, slipping in and out of consciousness, that’s all you want—to see your mother.

And that’s when Ruth Burks walks into your room. She’d been seeing a friend with cancer, was curious about the big, red bag hanging from your door, signifying “danger,” and was appalled at the nurses’ attitude when she asked them questions about you and the disease that’s killing you, AIDS. She got your mother’s phone number from the nurses, called her, and was hung up on. She called back, and your mother told her that she didn’t care; she wouldn’t even claim your body after you were dead.

You’ve never met Ruth Burks, but you’re so ill that when you see her, you say, “Oh, momma. I knew you’d come.” She takes your hand and says, “I’m here, honey. I’m here.”

Ruth Burks stays with you for the last 13 hours of your life.

That was the beginning of Ruth Burks’ mission. She realized that many, many people dying of AIDS were being ignored, reviled, and left to die alone. She thought she could help.

In the decades after that, Burks stopped concentrating on her budding real estate career and took care of over a thousand people who were dying of AIDS. Almost all of them were gay; almost all of them had been abandoned by their families. But they had Ruth Burks.

She solicited donations from gay-oriented organizations around the state and otherwise used what little money she had to take patients to appointments and help get them medications, even stockpiling “AIDS medicine” in her house from patients who had died. She stayed with patients when depression hit. And she arranged for their funerals.

As a result of a family squabble, Burks’ own mother had bought 262 plots in the local cemetery (to keep some members of her family from being buried near the others!). Now, Burks used those plots for the bodies or the ashes of dozens of AIDS victims. Despite Burks’ pleading, few families would even claim the ashes.

“I tried,” says Burks. “They hung up on me. They cussed me out. They prayed like I was a demon on the phone. . . . Just crazy.”

It was not a fun life—watching people slowly die (some of them wasting away to below 60 pounds), helping them fill out their own death certificates, and sometimes attending several funerals a day. And she was constantly harassed. After signing checks to pharmacy clerks, she was told that she had to keep the pen. “They didn’t want it in their building,” she says. “They would come out with a can of Lysol and spray me out the door.” Crosses were burned in her yard. Her church cast her away, its members even refusing to touch the coffee that she made for events. Burks’ daughter would often help her in the cemetery. As a result, “My daughter was never invited to a birthday party. All because I was helping people with a virus.”

But Burks knew that what she was doing was right. Her involvement even extended lives. Research from the Centers for Disease Control showed the average life span for people living with AIDS; those under Burks’ care were living two years longer than that average.

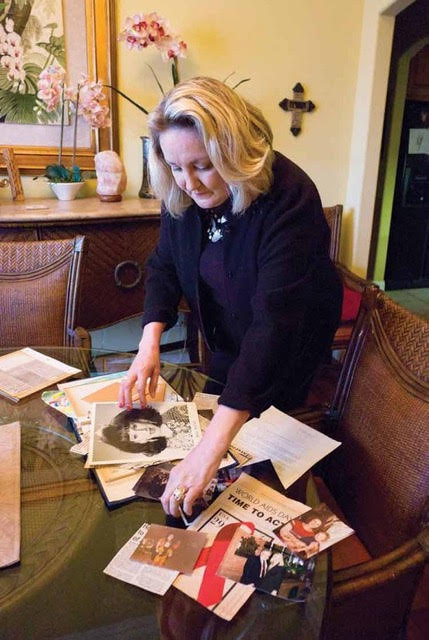

Burks went on to serve as a White House consultant on AIDS education. In 2010 she had a stroke but eventually recovered enough to talk, to feed herself, to read, and to write. She continued to be a forceful advocate for AIDS education and care. As recently as 2013, she supported three foster children who were removed from a local elementary school after school officials heard that one of them might be HIV-positive.

Now living a quiet life, Burks is loved by many. A friend who lost a partner to AIDS told her, “There wasn’t a doctor. There wasn’t a nurse. There wasn’t anyone. It was just you. . . . You loved them more than their families could. You loved them more than their church could.”

She sometimes wonders if she’d be living more comfortably now if she had continued with her real estate career, and she thinks that her stroke was probably caused in part by all the stress she’s endured. But Burks has no regrets. “We have to stick together,” she says. “We have to bond together and we have to take care of each other.”